Mid-Century Makeover

April 1, 2019

From the April/May 2019 issue of

Sactown Magazine.

By Hillary Louise Johnson

In 1959, two ambitious young architects and one soon-to-be-world-famous artist finished work on a building that caught the eye of the design world and introduced this city to the “International Style” that was sweeping America at the time. Today, that mid-century modern edifice, the original headquarters for the Sacramento Municipal Utility District, is about to be born anew after an $86 million face-lift. Turning 60 has never looked so sexy.

When the Sacramento Municipal Utility District’s headquarters was completed in 1959, the audaciously modernist building shot the young architectural firm of Dreyfuss & Blackford to fame, landing them a raft of awards, the front page of The New York Times’ real estate section, and the May 1961 cover of Architectural Forum magazine. But as any innovator will tell you, the birth of a landmark, while glorious in retrospect, is in reality fraught with anxious, do-or-die moments of truth.

“I was terrified,” says artist Wayne Thiebaud, describing one such hold-your-breath hat trick late in the construction process, when workers turned their hoses on Water City, his 250-by-15-foot mosaic mural, washing away the layer of molasses-like adhesive and butcher paper that had kept the hundreds of thousands of tiny glass tiles stuck together on their journey from the fabricator’s shop in Italy to their installation on the new SMUD building’s ground-floor exterior.

That protective coating had kept Thiebaud from seeing whether the artwork faithfully reproduced the life-size template the young painter and art teacher, with the help of one student, had created by projecting the original sketch onto the wall of the Sacramento City College gymnasium, one 3-foot section at a time. So Thiebaud had no idea whether the big reveal would turn out a triumph or a disaster. His friends, architects Albert Dreyfuss and Leonard Blackford, had taken a chance in hiring an unknown for this big job, just as SMUD had taken a chance on hiring them. As it turned out, he needn’t have worried.

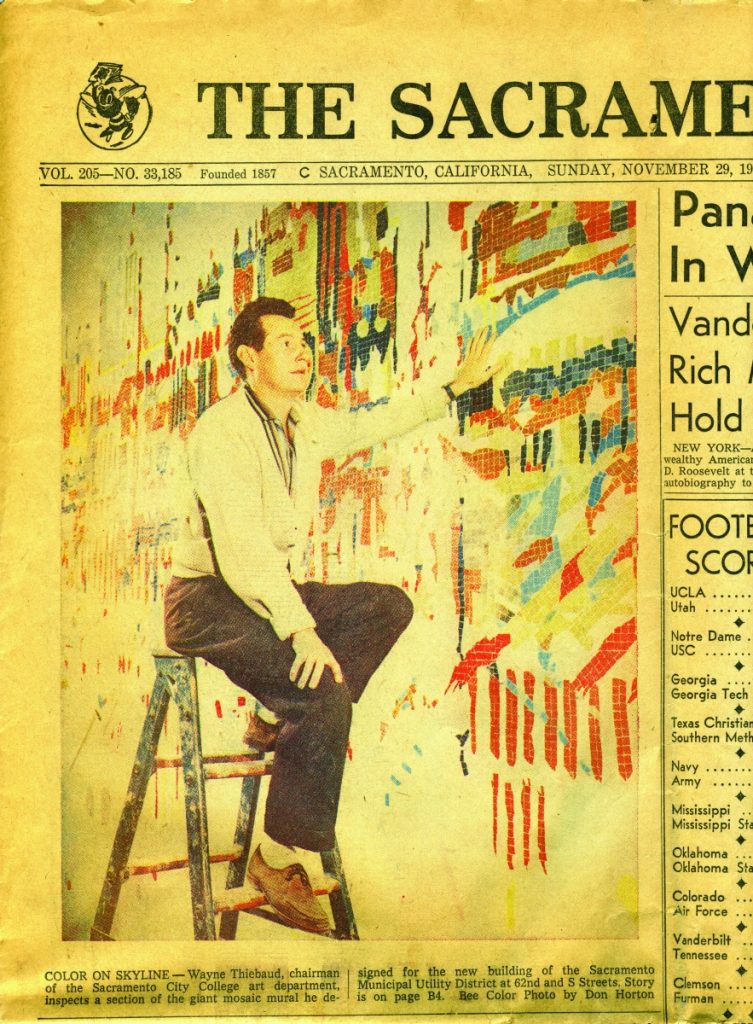

A photograph of artist Wayne Thiebaud with his mural mosaic for the original SMUD headquarters graces the front page of The Sacramento Bee on Nov. 29, 1959. (Courtesy of the Thiebaud Family)

“It was a miracle,” Thiebaud says now, describing how the finished work emerged magically from the detritus, just as he’d envisioned. Water City, which wraps around a large portion of the building’s base, is an Abstract Expressionist masterpiece, a detailed, meticulous, yet joyously explosive jazz interpretation of a meandering, inkblot-like suggestion of Sacramento’s cityscape reflected in a body of water. It remains Thiebaud’s one and only large-scale public installation, completed just a few years before the New York art world caught onto his painterly cakes and pies, and decades before he became one of the highest-grossing living artists in the world—which he still is today at 98.

Nineteen fifty-nine, however, was Dreyfuss and Blackford’s year. Their first project as partners was nothing short of a triumph, and it came during a time that marked the apex of enthusiasm for post-war urban renewal—for better or worse. Sacramento saw a little of each at the turn of that decade, with the first proposal for a new freeway to slice through downtown, the opening of the Arden Fair mall, and a bevy of office buildings sprouting along the new Capitol Mall, where 200 structures comprising a handful of ethnically and economically diverse neighborhoods had just been razed.

Meanwhile SMUD needed a new headquarters. The utility’s GM, Paul Shaad, had a reputation as a hands-on guy, and lore has it that he was impressed when he dropped in on one of Dreyfuss and Blackford’s construction sites and saw Blackford on the rooftop, overseeing the details. So despite the pair’s lack of experience working at such a scale, Shaad hired them to design a new 130,000-square-foot headquarters for a site at the edge of East Sacramento.

Wayne Thiebaud’s Water City is an Abstract Expressionist masterpiece, a detailed, meticulous, yet joyously explosive jazz interpretation of a meandering, inkblot-like suggestion of Sacramento’s cityscape reflected in a body of water. It remains the artist’s one and only large-scale public installation.

The structure they gave him did not disappoint; it was such an exemplary model of form and function that it would stay in continuous use for well over 50 years—right up until it closed in December 2015 to undergo an $86 million renovation and revitalization. Newer earthquake safety requirements meant that it had to be retrofitted eventually for SMUD to continue occupying it, and current building costs made restoring it more economical than new construction, so bringing the beloved edifice back to its former glory was a win-win for the company and its rate payers (having grown to over 2,000 employees, SMUD—which is the sixth largest publicly owned utility in the country—had built a new 177,000-square-foot building next door in 1995).

When the original headquarters reopens this July to welcome back the 430 employees who call it home (with room now for more), upgrades will include restoration of the original façades and grounds, historically accurate yet ergonomically up-to-date interiors, modernized mechanical systems for LEED Gold certification, and a brand-new addition to meet the need for contemporary, flexible workspaces. And leading the revitalization efforts, fittingly, is the current team at Dreyfuss & Blackford Architecture.

Albert Dreyfuss and Leonard Blackford were professional soul mates who met in 1952 when they bought two of the city’s first modernist ranch houses across the street from each other in Arden-Arcade. Both were World War II vets who served in the Pacific theater and got their architecture degrees in the 1940s (Dreyfuss, a Louisianan, from the University of Illinois, and Blackford, a California boy, from UC Berkeley). The neighbors bonded over the precepts of modernism, and when Dreyfuss started a firm of his own, he hired Blackford. The two made a dynamic duo: Dreyfuss the silver-tongued visionary and client-wrangler, Blackford the detail-driven genius, and when they took on SMUD, they became equal partners in the business.

The pair were also members of a local design intelligentsia, along with Thiebaud. “We had a little group that got together and talked about modernism,” the painter fondly remembers. “When Don Birrell was acting director of the Crocker Art Museum, we met there on occasion to talk about design and what we might be able to do in Sacramento to get people interested.”

Thiebaud’s 250-foot-long “Water City,” which is being carefully restored, covers three-quarters of the south wing’s base. (Courtesy of Dreyfuss + Blackford Architecture)

Birrell, an early student of Danish modernism, left the museum in 1953 and became the design director for the original Nut Tree. The erstwhile roadside dining and entertainment complex in Vacaville, as dreamed up by Dreyfuss and Blackford, was busy breaking design barriers in an effort to keep surprising and delighting generations of California road-trippers—long before outlet malls and big box stores crowded it out. Later, the duo’s daring concept for the Nut Tree’s coffee shop—which combined concrete slabs with a soaring, conical ceiling and a gallery area furnished with bespoke sofas by Charles and Ray Eames—landed them in Architectural Record. In 1959, their long, linear courtyard design for the swanky, swingin’ Mansion Inn in downtown Sacramento, where members of the Rat Pack would congregate to clink martini glasses throughout the 1960s, won them a prestigious American Institute of Architects award.

“Len Blackford was very interested in avant-garde architecture,” Thiebaud recalls. He adds that the group that met at the Crocker didn’t just talk about cutting-edge concepts, but also brought in psychologists and philosophers to talk about the human side of their profession. And it’s that humanistic side that made Blackford’s take on modernism “a little richer, not so stark,” according to Thiebaud.

The International Style building’s façade features “fins” that rotate throughout the day to block direct sunlight. (Courtesy of Dreyfuss + Blackford Architecture)

Dreyfuss and particularly Blackford were admirers of Mies van der Rohe and the International Style, which emphasized volume over mass and regularity over symmetry, and eschewed decoration. The concept of favoring volume over mass led many architects of the time to float upper floors above pedestrian breezeways and plazas, as in Mies’ Seagram Building and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s Lever House in New York. But these grand public spaces defined by great swaths of steel and glass were all about carving new vistas out of the urban landscape—removing mass from the streetscape and replacing it with volumes of air. The SMUD site was at the time quite verdant and serene.

Dreyfuss and Blackford—perhaps because of those rap sessions with psychologists—chose to embrace this gentle siting and make their design more subtle and approachable, including lush, Japanese-inspired landscaping and art in their plan for the public spaces and entrances. They divided the square footage into two asymmetrical slabs, one long, one low, connected by elevators, passageways and a service shaft. On the exterior of the two blocks, they chose to emphasize pattern, cleverly enlisting exposed structural elements to create pleasing repetitions. Where the façade of the building faces the sun, adjustable vertical aluminum “fins” driven by hidden mechanisms rotate all day to block direct sun while letting indirect light flood in. Precast concrete panels were framed in aluminum to create regularity and a sense of texture.

Compared to its curtain-walled cousins on the East Coast, SMUD’s façade could almost be called busy, were it not for the harmony of each element’s proportions. It was still an exemplar of International Style, so much so that the building’s application for national landmark status, which it achieved in 2010, stated that Dreyfuss and Blackford’s work in the form “transformed Sacramento’s architectural landscape.”

“That is probably my favorite building,” says Michael Heller, a second-generation local developer who most recently masterminded the Ice Blocks complex on R Street. “It’s resonated with me for a long time.”

Heller was not yet born when his father, Michael Heller Sr., a fan of modern art and architecture, became the builder on the SMUD venture, working alongside his good friend Wayne Thiebaud and his favorite architect, Len Blackford, on a dream project.

Dreyfuss and Blackford were admirers of Mies van der Rohe and the International Style, which emphasized volume over mass and regularity over symmetry, and eschewed decoration. The concept of favoring volume over mass led many architects of the time to float upper floors above pedestrian breezeways and plazas.

“It’s ageless architecture and design, just a classic. The SMUD building was the inspiration that got me and Paul Thiebaud, Wayne’s son, wanting to do another generation’s version of it,” says Heller of the planned Tribute Building in honor of Mike Sr. and Wayne. Paul, who was a noted art dealer, died in 2010, but Heller still plans on completing the building, which will feature Wayne Thiebaud’s second building-scale mural, a reproduction of one of the painter’s famous Delta landscapes.

Inside, the original SMUD building continued the exterior’s textural patterns. Images from the early ’60s show lighted ceiling panels extending in a syncopated scatter print motif, creating interest along with the shadows cast by the exterior fins—in those photos, happy secretaries are seen typing at freestanding desks in an interior landscape that seemingly sweeps on for acres.

Times change, of course, and more recent pictures of the building’s interior reveal that over the years, the open plan’s natural light was obstructed by the addition of a maze of beige cubicles; the original lighting design was compromised in the name of energy conservation; and carpet replaced the original vinyl—in all, the pre-renovation space wore a thick coating of beige blah by the time it closed for the rehab.

Dreyfuss + Blackford Architecture’s design for the renovation includes a new 12,000-square-foot glass-walled tower between the two wings of the original building. According to rules governing the building’s landmark status, any such additions must be in a distinct style. (Rendering by Dreyfuss + Blackford Architecture)

“Dreyfuss and Blackford designed this like a machine. There is no wasted space, so it’s a challenge to fit everything in,” says Kristopher Barkley, the current president and design director of Dreyfuss & Blackford Architecture, pointing out the devilish details during a site tour in February. In the ground-level boardroom, for instance, where the floor had to be raised for ADA compliance, “we raised the ceiling to keep the same proportions,” he says.

Gesturing to an open atrium where the buildings connect, he says, “This encourages interaction between departments and a meeting point for chance encounters and conversations—it makes it a modern office.”

The atrium is the heart of a new 12,000-square-foot addition, a narrow glass tower nestled between and linking the two original blocks that expands on the original service core to include glass-walled meeting rooms. It’s also another opportunity to carry forward the building’s legacy, providing space for another dramatically large mural—artist to be determined (Thiebaud’s still painting, but he’s a little more expensive now).

“There is also the possibility of a suspended sculpture, given the height of the atrium,” says Barkley. Something like the Red Rabbit, perhaps? You know, the one that hangs at the Sacramento International Airport—another little Dreyfuss & Blackford project you may have heard of.

There are no plans as of yet for SMUD’s new facilities to be open to the public to tour, but if it’s any consolation, remember that as a public utility, it is owned by its rate payers, so if that’s you, congrats on owning a piece of architectural history—along with a terrazzo tile or two of an early Wayne Thiebaud.