Nut Tree Forever

March 3, 2021

From the cover of the March/April 2021 issue of

Sactown Magazine.

By Leilani Marie Labong

If you lived in Northern California any time from the ’50s to the ’90s, your memories likely contain vivid flickers of Vacaville’s Nut Tree—the roadside oasis that lured generations of kids and adults alike. Was it an amusement park so wondrous that even Walt Disney himself visited? Or was it California’s original farm-to-fork capital? Or a modern art and design mecca that was first to bring mid-century Eames furniture to the NorCal masses? It was all of that and more. It was also, as it happens, the creative vision of a group of Sacramento artists, designers, architects and, yes, candymakers. And now, in 2021, it’s turning 100. Let’s all jump on that miniature train—you know the one—and take a ride back in time for a Kodachrome encounter.

For Sacramentans of a certain age, Vacaville’s Nut Tree of bygone decades was a magical adventure land where stuffed animals were life-size in stature, handmade rocking horses inspired pretend-gallops into the sunset and pinwheel lollipops seemed as big as flying saucers. Where a miniature train took the scenic route from the toy store to the on-site airport, and stunt-filled air shows were grand marshaled by aeronautical legends like Chuck Yeager and Neil Armstrong. Not far from the roaring acrobatics, the planes’ plumed counterparts—exotic birds, from a golden pheasant to a bossy, bright orange Andean cock-of-the-rock—spread their wings in a lofty and leafy aviary, a unique gateway to the signature restaurant.

A far cry from its modern-day iteration as a chain-store bonanza, the Nut Tree of yesteryear was a pop-hued funfair on westbound I-80 that drew parallels to Disneyland by noteworthy architects of the time (and like Disneyland, it took its cues, in part, from the celebrated Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen, an amusement park that opened in 1843), but to label it an amusement park doesn’t do it justice. It was, as they say, everything.

“Growing up at the Nut Tree was magical,” says Diane Power Zimmerman, a third-generation member of the Power family, founders of the Nut Tree. She started selling toys there when she was 12, also the age her siblings and cousins (17 of them in all) started working in the family business. “We tested every new attraction. We inaugurated the first trains and were always the first in line for fireworks shows. Normal for us was having breakfast next to the tropical birds and then piling onto the school bus. But still, I’d always marvel at the excitement of a child who came running into the toy store to buy a train ticket and stopped in awe to look at a life-sized stuffed animal. That was the real magic of the Nut Tree.”

A colorized photograph featuring an aerial view of the Nut Tree Plaza in 1964 (Photo by Don Horton courtesy of the Vacaville Museum. Colorization by Dr. Melvin Hale.)

No mind was ever paid, at least not by these otherwise spellbound children, to the high level of modern design that was also on display, with spaces bounded by glass walls, soaring ceilings and crisp lines, or to the thoughtful cuisine—a prototype of today’s sweeping farm-to-fork movement and a calling card for this glorious highway rest stop. Sacramento designer Curtis Popp, who recently turned 50 and so came of age during the Nut Tree’s prime, admires how the Nut Tree of his youth wasn’t, as he says, a “caricature” of an amusement park. “It didn’t placate to us kids with only primary colors or too much goofy stuff,” says Popp. “It was approachable without being corny.”

This is the playful mecca of modernism—or a mecca of playful modernism, your choice—that lives in the technicolor memories of local Gen Xers and baby boomers, and many other nostalgic Northern Californians who grew up traveling the I-80 corridor between San Francisco and Lake Tahoe during the Nut Tree’s mid-1950s-to-mid-1980s heyday. Architect Ron Vrilakas was raised in West Sacramento and connects visits to the Nut Tree with family travel. “It was a very special place for me as a kid because it always signaled the start of a fun adventure, a family weekend away,” says Vrilakas. “I’ve never experienced anything quite like it since.”

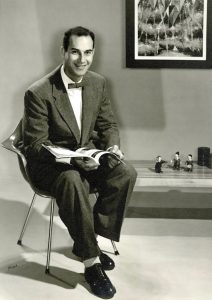

Don Birrell in 1952 when he was the director of the Crocker Art Museum, a year before he became design director of the Nut Tree (Portrait courtesy of the Vacaville Museum)

The singular Nut Tree phenomenon was crafted in large part by a team of idealistic Sacramentans brought together by a once-in-a-lifetime starry alignment and a particular kind of ambition and early-career cachet: Local architects Albert Dreyfuss and Leonard Blackford designed the Mies van der Rohe-inspired SMUD headquarters in Sacramento—finished in 1959 and now listed on the National Register of Historic Places—shortly after they signed on to the Nut Tree project in 1958. The Nut Tree’s builder, Mike Heller Sr. of Continental Heller Construction, would culminate his long career with the award-winning restoration of the State Capitol building, completed in 1982. Robert Deering, the inaugural chairman of the landscape architecture department at UC Davis from 1950 to 1957, was the Nut Tree’s landscape architect and even designed a car park for the complex that’s recognized as one of the first tree-shaded lots in the country.

But the Sacramentan with perhaps the greatest impact on the Nut Tree was its design director Don Birrell, who had previously held another prestigious position as the director of the Crocker Art Museum from 1951 to 1953. The River City wunderkind grew up in West Tahoe Park and was an alum of Sacramento High (where he was one of the yearbook’s arts editors) and Sacramento Junior College (where he was president of the arts league). “Our whole family thinks of Don Birrell as our hero,” says Zimmerman. “He was such a smart man and brought distinction to the work.”

The Nut Tree displayed such thoughtfulness under Birrell’s nearly four-decade tenure that it became a twinkle in the eyes of design scholars for decades to come, including Charles Moore, a founding architect of the iconic modernist Sea Ranch enclave on the Sonoma Coast. He famously admired the lighthearted vernacular of Disneyland’s exaggerated edifices, and wrote of the Nut Tree with equal fondness in a 1965 essay published in Yale’s architecture journal Perspecta. “It offers the traveler a gift of great importance. It is an offering of urbanity, of sophistication and chic, a kind of foretaste, for those bound west, of the urban joys of San Francisco.” In 1978, the San Francisco Chronicle called the roadside attraction an “oasis of taste”—a metaphorical achievement earned by coming a long way from its literal seed of origin.

*****

In 1859, a black walnut was planted on a Vacaville farm by a pioneer woman named Sallie Fox. She dutifully carried it in the pocket of her gingham pinafore while on an eventful year-long wagon train from Iowa to California, where some family had already settled during the Gold Rush. The seed eventually grew into the tree that provided shade for the first iteration of the Nut Tree, a roadside stand made of eucalyptus poles and palm fronds that opened on July 3, 1921. There, Edwin “Bunny” Power (so nicknamed for his ear-wiggling talents) and his wife Helen (Sallie Fox’s second cousin) sold fruit from the family’s 135-acre plot, located along what was then US Highway 40 (now Interstate 80).

A colorized postcard of the Nut Tree circa the 1940s with its promise of “adventures in good eating” (Postcard courtesy of and colorized by Dr. Melvin Hale)

They charmed travelers with a truly pleasant pit-stop experience: decorative flowers created a genteel atmosphere, fresh water was on tap for overheating cars and their equivalently parched passengers and the sprawling tree canopy offered a shady spot to sit in one of the provided rocking chairs and read a copy of The Saturday Evening Post, also regularly available. On ad hoc sawhorse tables, Bunny and Helen, a Power couple in name and ambition, displayed dried figs for sale, as well as sacks of fresh ones—produce at peak ripeness was always packed at the bottom of the bags so that customers would remember the stand fondly as they polished off their purchases further down the line.

“It was their style to do things right, to give people a little extra,” says Heidi Casebolt, registrar at the Vacaville Museum, whose new Nut Tree Centennial exhibit opened in March. On view through Jan. 9, 2022, the display animates a timeline of the Nut Tree’s history through memorabilia from the museum’s vast archive of ephemera, curios and other keepsakes donated by the Power family, former employees and members of the community.

Under the founding couple’s philosophy of generosity, the modest fruit stand expanded beyond the shade of the black walnut tree to include a tea room, restaurant, flower shop and gift shop within the first two decades. A new sign—“Adventures in Good Eating”—was placed at the base of the arboreal landmark in the early 1940s, and making good on that promise were the “boneless chicken tamales” and pineapple slices with mallow sauce, a complimentary appetizer that made enough of an impression that many remember it to this day.

Poisoned by decades of car exhaust, Sallie Fox’s walnut tree was regrettably felled in 1951. (For what it’s worth, a table-sized slab cut from the original tree trunk is among the exhibit’s artifacts.) Still, the action may have symbolized a new chapter. Tree or no tree, that’s when the business really started, er, branching out.

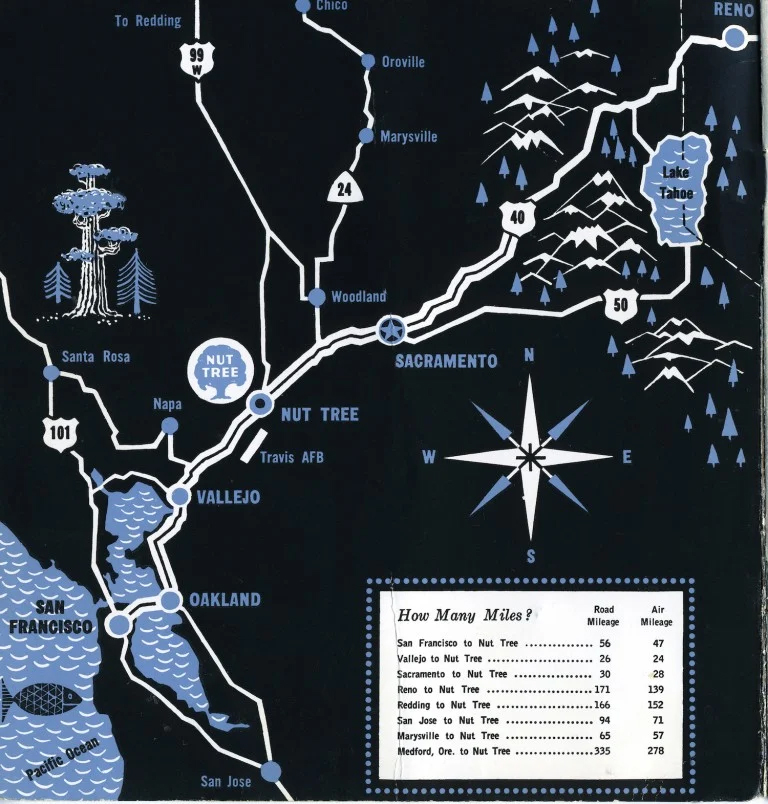

This map by Birrell, which indicates Nut Tree’s proximity to nearby NorCal locales like Sacramento, San Francisco and Lake Tahoe, appeared inside an iteration of the Nut Tree menu.

Zimmerman disputes the widely reported account that Bunny and Helen’s three adult children—Bob, Ed Jr., and Mary Helen—poached graphic artist Don Birrell from the Crocker Art Museum in 1953. He was then the museum’s rookie director, hired at the age of 28, shortly after he graduated in 1949 from the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles (which eventually became CalArts, the Disney-backed school that has long produced many of its Imagineers, including Mary Blair, best known for her design of the It’s a Small World ride). The Power siblings needed a little help with the Nut Tree’s graphic art and marketing materials. They had been keeping an eye on recent exhibitions at the Crocker and could tell that Birrell had a line on emerging local artists, including painter Wayne Thiebaud, who was just 30 years old when Birrell organized his solo debut at the museum in 1951, auspiciously minting his career. (Birrell would later mount another Thiebaud exhibit at the Nut Tree in 1960.)

“So they met with Don to see if he knew of anyone who would be interested in working on graphics at the Nut Tree,” says Zimmerman, Bob’s daughter, who is halfway through writing a book called Nut Tree: From California Ranch to Design, Food, and Hospitality Icon, which she plans to self-publish sometime this year. “Two weeks later, Don came knocking on their door to tell them that he was the right man for the job.”

*****

“Don is hard to describe,” says Shawn Lum, the former executive director of the Vacaville Museum and an 11-year veteran of the human resources department at the Nut Tree, of her late mentor. “He appreciated fine things. He was well read and appreciated art in the highest sense.”

Birrell, who served as the Nut Tree’s design director from 1953 to 1990, lived just one block away from the museum in a mid-century house he designed with the help of Dreyfuss & Blackford. Even in the leisure of retirement, he would put on his trademark houndstooth sports coat and stop by to offer practical words of improvement.

“Turn on the exterior lights on gray days,” he once told Lum. “It will lift people’s spirits as they pass by.” A simple point well taken, but there was often more to impart: “It’s important for you, as the director of the museum, to be aware that when it’s a gray day, people are influenced by something welcoming.” Lum’s fondness for Birrell is clear, a warmth she attributes to their shared love of art and design. To this day, she can’t let a single envelope leave her desk without carefully considering its white space, the placement of the addresses, the font and overall readability—schematic considerations wedged deep into her psyche by Birrell’s fastidiousness about such details.

A photo from the early ’70s of the Nut Tree sign that faced I-80 (Photo courtesy of the Vacaville Museum)

A 2006 article in the Vacaville Reporter, written shortly after he died at age 83 of pneumonia (and perhaps a broken heart; Lum says that he faded quickly after his wife, Doris, passed away the year before), speaks of his “sharply defined logos,” and how they informed “Nut Tree ‘look.’ ” Assisting Birrell in this eye-popping pursuit was a small design department that included local artists Roy Lee and Wally Remington. So successful were they in toeing the line between playful and polished that Charles Moore described the graphic design at the Nut Tree as having “consummate sophistication and great flair.” From the evenly scalloped edges of one of the most recognizable Nut Tree logos to the simple sketches of pineapples on a ’70s-era restaurant menu to the lions’ manes and elephants’ ears interpreted as perfect circles on fun photo-op walls throughout the park, stripped-down forms and riotous color palettes made the Nut Tree “look” exceptionally—some even say aggressively—accessible.

UC Davis design professor James Housefield explains how the roadside complex even played a role in cementing the hippie-era catchphrase of “peace and love.” “Don Birrell’s design work for the Nut Tree had much in common with the vibrant flower power aesthetics of the 1960s, and may have been one inspiration for this global style,” says Housefield, who is dedicating the final chapter of his forthcoming book, Swimming at the Museum, and Other Ways of Seeing: The Emergence of Exhibition Culture in and Around San Francisco (projected to be released by 2023), to the Nut Tree of yesteryear.

The Nut Tree restaurant, seen here in the 1970s, was furnished with chairs designed by Charles and Ray Eames. (Photo courtesy of the Vacaville Museum)

Housefield also notes that in the 1950s, the Nut Tree served its “49-Way Sundae” with colorful paper “fun flowers,” which soon became one of the park’s staple souvenirs. “As their packaging proclaimed, these ‘paper flowers … became the symbol of a whole generation of American youth,’ asserting that they inspired the ubiquitous flower stickers and decals of 1960s youth culture,” he says.

Sculptor Stan Bitters further rooted the flower-power theme with his oversized ceramic blossoms of three-dimensional, mandala-like intricacy and color, which were “planted” in gardens around the property. “Let’s not forget that the Nut Tree really came up in the era of Pop Art ,” says Housefield. “The flower an aesthetic that can be rapidly understood and is very welcoming for all audiences.” Such youthful and exuberant blooms were often pleasingly symmetrical and bulbously cartoony, and could be found on Nut Tree posters and signs, including a horizontal freeway-facing piece on the exterior of the restaurant/retail building fabricated by Federal Sign (née Electrical Products Corporation), crafters of iconic neon throughout the region, including Gunther’s “Jugglin’ Joe” and Tower Records’ “Dancing Kids.” On a tinier scale, the finishing touch for the restaurant’s popular Chinese-inspired Chicken Almond entrée was a small flower garnish cut from an orange rind—the Nut Tree’s optimistic outlook epitomized in one fell flourish.

*****

Some of Birrell’s rules for a tabletop setting at the Nut Tree restaurant were as follows: The plate should be fixed square to the chair. The fork and the knife need to be a knife’s length apart. The condiment dish is always to be placed at 12 o’clock, above the plate. The tall peppermill is to be situated to the left of the short salt shaker. The coffee cup should be located at the spoon’s head, with the handle turned to 4 o’clock. One creamer per person. “And so forth,” says Heidi Casebolt, who recreated one of the restaurant booths for the Nut Tree Centennial at the Vacaville Museum, complete with its casbah-like overhead draping of flashy fabric and full table setting featuring the original white porcelain plates by Dansk and a few of the Eames armchairs, then an icon-in-the-making of mid-century design produced by the Herman Miller furniture company.

These molded fiberglass seats were designed by Charles Eames and his wife Ray—a Sacramento native born as Bernice Alexandra Kaiser in 1912—who got to know Birrell and the Power family, heavily influencing style at their private homes as well as at the Nut Tree. The Case Study Houses, the experimental American residences envisioned by the dignitaries of mid-century design—from William Wurster to Eero Saarinen to the Eameses—informed the architecture of the glass-walled Nut Tree toy store and Bunny and Helen’s Vacaville home, appointed top to bottom in Herman Miller furniture. The Nut Tree gift shop was the first Herman Miller dealer in Northern California, and sold the Eames armchairs alongside everything else featured at the rigidly organized restaurant tables—from the silverware to the peppermills to the Dansk plates, which proved to be a popular selection for wedding china. The aspirational, design-forward “Nut Tree look” could be recreated at home, a marketing strategy that may be commonplace today, but back then was cutting edge.

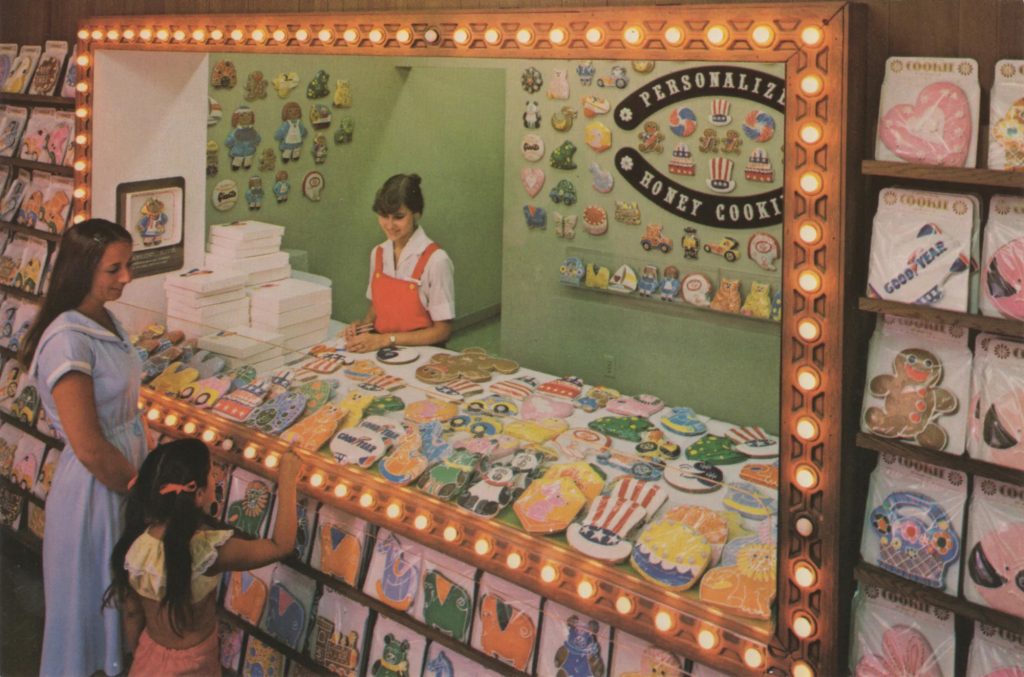

Oversized honey cookies, which were made based on a Birrell family recipe and could be personalized, were a big part (literally) of the Nut Tree lore (Photo courtesy of Gretchen Steinberg)

“I see the Nut Tree as one of the first examples of a unified design approach, which these days you’d probably call a ‘branded environment,’ ” says UC Davis design professor Timothy McNeil. He and his colleague James Housefield are currently planning a Nut Tree exhibit, which they hope to mount at the school’s Manetti Shrem Museum by next year. “A Nike store would be a good example. Granted, the Nut Tree was a different type of experience, but the idea still rings true.” (The Nut Tree was also an unwitting prototype of a trendy modern-day concept called “the experience economy,” in which businesses holistically create pleasant memories for customers through goods and services.)

Birrell’s “design micromanagement,” as McNeil describes this atomic level of direction, also included the food presentation. The Chicken Almond, for example, resembled a flower growing in grass, or the sun shining on a garden: orange slices edged a mound of rice, fresh green snow peas were added to the chicken almond stir-fry, and disposable chopsticks in a red paper sleeve were placed on the right side of the plate, always on the rim.

The composition of another signature dish, the round fruit platter, was dictated by complementary colors: golden pineapple slices across from—never next to—blackberries; dark red cherries diagonal from green grapes. And since the center was filled with a bowl of sherbet (or ice cream or cottage cheese), according to Nut Tree Remembered: The Cookbook, a best-seller at the Vacaville Museum gift shop, the overall effect was again botanic.

In 1960, Birrell acquired a small Sacramento candy shop, transferring its equipment and its candymaker, Art Mayland, to the Nut Tree. From hand-pulled taffies and hypnotic pinwheel lollipops to double-candy-coated freeze-dried strawberries and the gooey house-made caramel and fudge sauces ladled atop the specialty scoops that Gunther’s churned specifically for the Nut Tree, Birrell and Mayland worked together on an exquisite, real-life sugar rush to rival another confectionary of the moment, brought to life by Roald Dahl in his classic 1964 children’s novel Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

The Nut Tree gift shop, which was the first Herman Miller furniture dealer in Northern California, sold everything from Eames chairs to Dansk plates (Photo courtesy of Dreyfuss + Blackford Architecture)

One notable admirer of Birrell’s predilection for presentation was Wayne Thiebaud. The Sacramento artist and professor was a frequent visitor to the Nut Tree, stopping by on class trips to San Francisco art museums with his students.

“ was a very good friend, and we shared a love of working in the community and trying to elevate the character and look at the look of things,” he recalls. And as a well-established chronicler of all things sweet—Thiebaud’s Encased Cakes painting drew an $8.5 million sale at Sotheby’s in 2019—his artist’s eye picked up on Birrell’s artistic arrangements.

“He designed different ways of displaying candies, laying them out in beautiful arrangements—all kinds of suckers, cakes, cookies. He wanted to make it so that people couldn’t wait to pick them up. He thought they should be so well designed, so beautiful that they would be like art objects,” says Thiebaud, adding, “I’m sure it was an influence of some kind” on his own work of neatly arranged desserts.

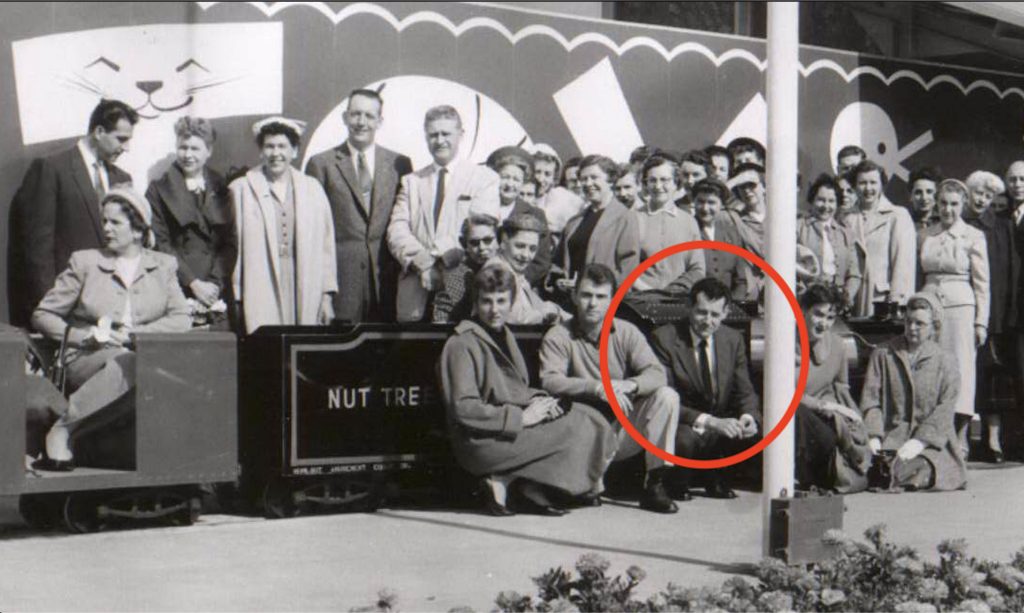

Wayne Thiebaud, circled, frequently took his art students to San Francisco museums, often stopping at Nut Tree along the way. Here he is in the 1950s with a class from Sacramento City College. (Photo courtesy of the Vacaville Museum)

The painter, who turned 100 last November, also fondly recalls the attention to detail in the restaurant, including the famous appetizer. “They would serve things on beautiful fig leaves, like pineapple with marshmallow drippings over it. Nobody ever forgot that,” he says, chuckling.

In the era of housewives liberating themselves from their kitchen shackles with easy-to-prepare processed foods, a phenomenon commonly attributed to the post-World War II economic boom, the farm-to-fork-style sourcing at the Nut Tree—Bob Power’s most influential contribution to the business—was also contemporary. The Nut Tree’s farmers tended 200 acres of fruit orchards and row crops to supply the onsite food programs, and in fact the train ride skirted this farmland on its route between the toy store and the airport. In 1978, former New York Times food editor Raymond Sokolov called the Nut Tree a “crucible of California style” and “the region’s most characteristic and influential restaurant.”

Sacramento’s godmother of Italian cuisine, the late Biba Caggiano, posted up monthly at the Nut Tree in the early 1970s to teach cooking seminars. Birrell designed double-sided cards detailing her recipes—from fagiolini all’olio e limone (green beans with oil and lemon) to a creamy carbonara—so the participants could recreate the dishes at home. And when Gov. George Deukmejian hosted an extravagant lunch at the State Capitol for Queen Elizabeth II in 1983, he requested catering by the Nut Tree restaurant, one of his personal favorites. The meal started with a salad sourced from the Nut Tree farm, followed by seafood crepes and mini croissants.

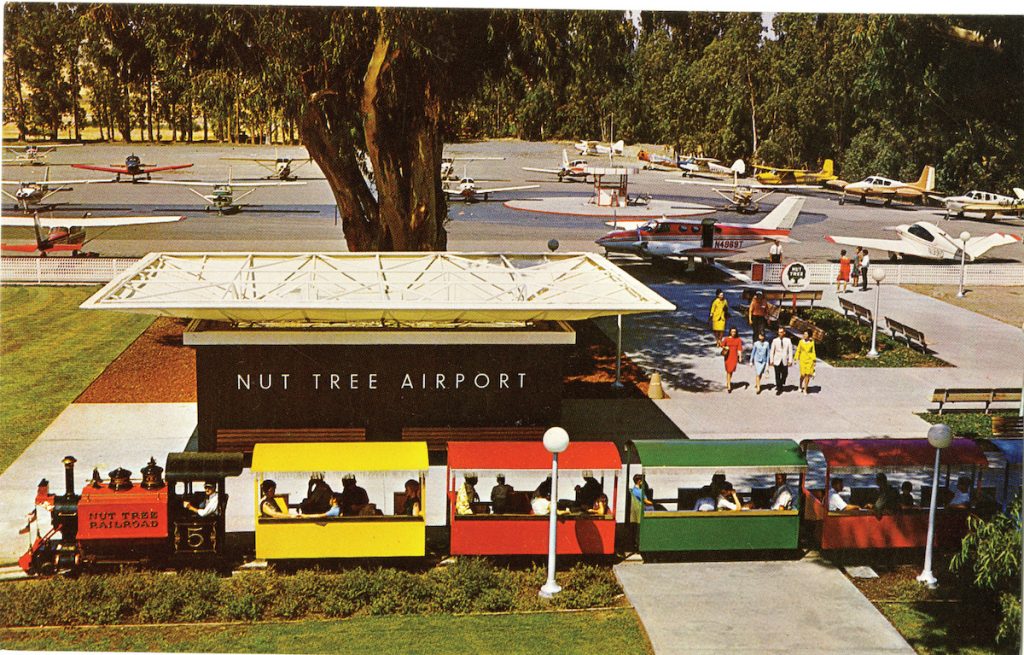

This 1975 postcard depicts the signature train that looped around the entire Nut Tree property, including the complex’s airport. The popular vehicle carried boldface names like Julia Child, Walt Disney and Shirley Temple. (Postcard courtesy of the Vacaville Museum)

“(Someone) asked Julia Child to critique the menu and she appeared on TV to do just that! In her unmistakable falsetto voice, she said that you shouldn’t serve a crepe and a croissant at the same time. It just wasn’t done,” says Tom Kassis, an 82-year-old Carmichael resident who was then the Nut Tree’s director of administration and present at the event. “However, I watched the queen closely. She ate everything that was put in front of her. If she knew of Julia’s , she didn’t pay any attention to it.”

Among the only fresh crops not sourced from the Nut Tree farm were the pineapples for that famous appetizer, always free because the fruit symbolized hospitality. “For many years, the Nut Tree was the second-largest (buyer) of pineapple from Hawaii,” says Kassis. (Pike’s Place Market in Seattle was the largest pineapple purchaser.) “And eventually, the Nut Tree became the quality standard for Dole. Their fruit was green, green-ripe, ripe and the Nut Tree.” In the spirit, it would seem, of those first fleshy figs at the bottom of the bag.

*****

If the Nut Tree seemed revolutionary, the golden age of air travel (1950s and 1960s) may have had something to do with it. In WWII, Ed Jr. learned to fly and service aircraft, and when he returned from his tour of duty, he bought a private plane. “The idea for a Nut Tree airport simply grew from there,” says Kassis. When the airport was built in 1955, the landing strip was just dirt. But once pilots began to enjoy the experience of flying into the Nut Tree, lights were installed, the runway was paved and a taxiway was added. Events began to transpire—the first Cessna air show took place in 1960, for example, and in 1982, astronaut Neil Armstrong was the guest speaker at the final (25th annual) Rotary Fly-In. Chuck Yeager, the Air Force pilot who broke the speed of sound in 1947, was also a keynote speaker at one of the Fly-Ins—he was a buddy of Ed Jr.’s and would often stop by the Nut Tree on his way to San Francisco from his home in Grass Valley.

A certain degree of swagger may have surged in a few Sacramento VIPs who were suddenly wont to make the seven-minute hop in their private planes for lunch at the Nut Tree—local developer Mike Heller remembers doing just that on Sundays with his late father, Mike Heller Sr., the project’s general contractor. “For an 8-year-old kid, pushing the plane onto the tarmac in Sacramento and then landing minutes later in Vacaville was really cool,” he says. “But the real fantasy was waiting at the Nut Tree.” Albert Dreyfuss and Leonard Blackford, the architects, did the same with their clients in the company’s Beechcraft jet. Pomp aside, the Nut Tree Airport—donated to Solano County in 1970 with a later agreement that the name live on—did mostly what airports do best: welcome the planes that make the world a smaller place faster than cars or trains ever could.

Then-Gov. Ronald Reagan and California first lady Nancy Reagan in 1967 at the Nut Tree, which also drew other political figures, such as Richard Nixon and Pat Brown (Photo courtesy of the Vacaville Museum)

Remember the orange slices arranged in petallike fashion on the Chicken Almond dish? Putting hot and cold elements together on the plate was a novel concept for the time, at least in America—Bunny and Helen brought the idea back from a vacation in Mexico. And those exotic birds in the aviary? Birrell wanted even more flashes of bright plumage, musing about them in a hand-illustrated memo to Shawn Lum in the human resources department. Soon thereafter, other birds of a feather, chosen by aviary keeper Bill Toone—who earned a master’s degree in avian biology from UC Davis and went on to become the youngest-ever curator of birds at the San Diego Zoo—would arrive from South America and other international locales.

Arts ambassadors, politicians and diplomatic dignitaries also landed at the Nut Tree, from Bing Crosby and Shirley Temple to Richard Nixon and Nancy and Ronald Reagan, who was reportedly partial to the train ride. In fact, none other than Walt Disney himself, a die-hard locomotive enthusiast, stopped in to ride the train and visit the park several times in the ’50s and ’60s, according to Zimmerman. Her uncle Ed Jr. rode the train with Disney and received personally signed photos for him and his kids as a gesture of thanks.

Another unlikely Disney connection: The Nut Tree’s longtime children’s entertainer—Purves Pullen, a puppeteer and renowned bird mimic—did much of the whistling and chirping for the birds in Disneyland’s Enchanted Tiki Room, a soundtrack that runs to this day.

The Nut Tree’s celebrated restaurant, a forerunner of today’s farm-to-fork movement, included a large glass-walled aviary filled with exotic birds. (Photo courtesy of Dreyfuss + Blackford Architecture)

Like Disney, Don Birrell fell in love with Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens, and after a 1957 trip with Ed Jr., Birrell recreated Tivoli’s four-sided, rocket-shaped plaza kiosks that were used as snack and souvenir stands—the marquee bulbs lining the nose cones captured the attention of visitors. So impactful was this simple discovery that decades later Birrell would refer the revelation to Shawn Lum one memorable gray day at the Vacaville Museum when such lights would have made a welcoming impression on passersby. In fact, the museum installed one of the Nut Tree’s original Tivoli-inspired kiosks on its front patio, using it to broadcast current and future events.

On another design scouting mission, Birrell visited Japan, whose ancient Buddhist traditions are synonymous with minimalism, an approach later co-opted by apostles of modern design and architecture. The Zen belief that beauty and satisfaction can be found within the void of nothingness seemed to be the perfect counterpoint to a lively amusement park—modernist design would be the quiet and aesthetically weighty element amid the frolic.

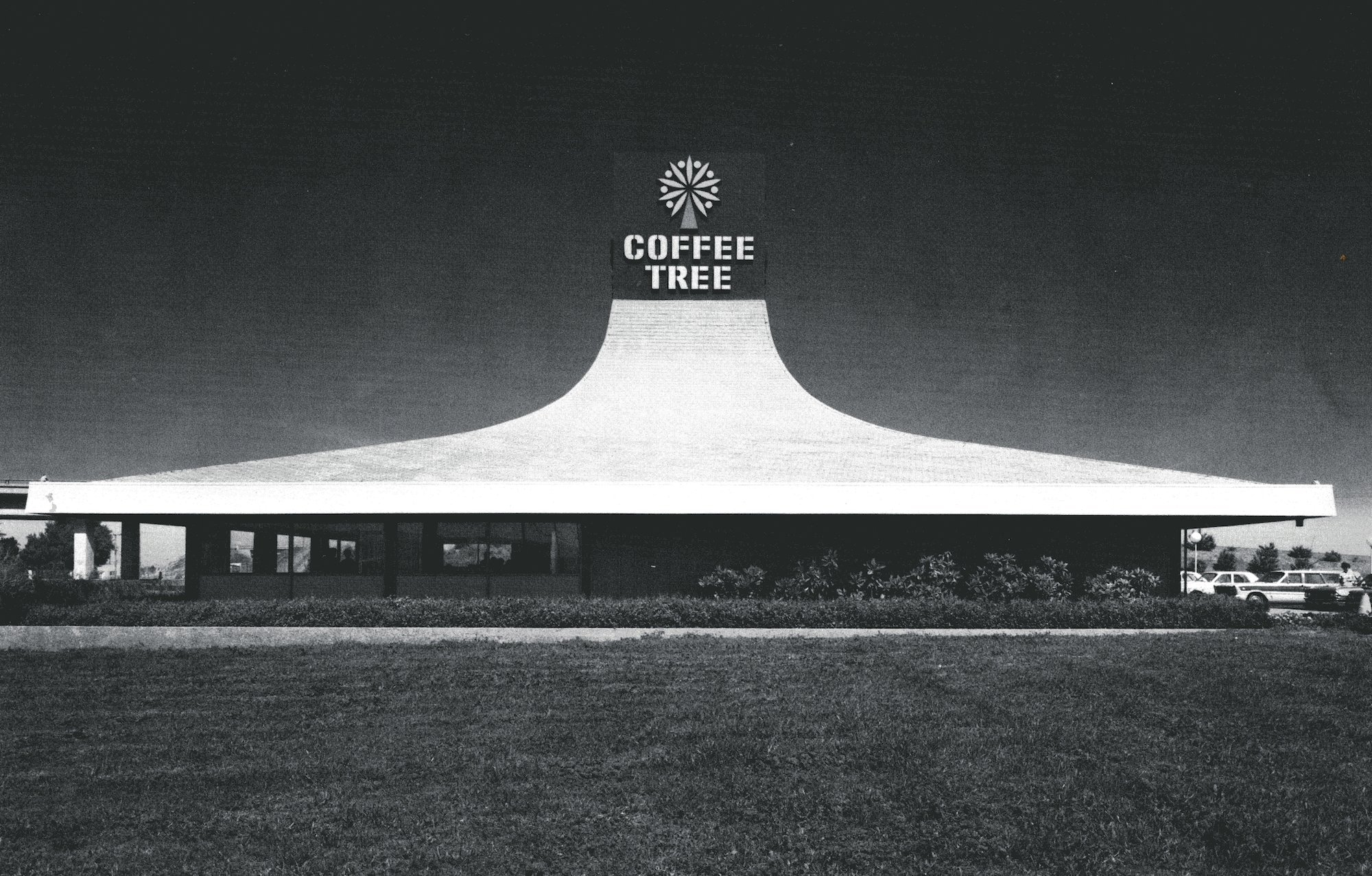

In 1958, when Birrell began collaborating with Dreyfuss & Blackford on the redesign of the 1940s-era restaurant, classic modernism was already in full effect in the Western world. Across the freeway, the dramatic and sweeping cupola of the Coffee Tree diner—completed in 1965 to ensnare eastbound I-80 drivers into the Nut Tree universe—earned Dreyfuss & Blackford an American Institute of Architects merit award in 1967.

The Coffee Tree restaurant, designed by Sacramento’s Dreyfuss + Blackford Architecture, was added to the Nut Tree universe in 1965. (Photo courtesy of Dreyfuss + Blackford Architecture)

Still, the most emblematic of the firm’s architectural modernisms at the Nut Tree remains the main complex’s signature restaurant, a magnificent space of full-height glass, natural light and plenty of fresh air. The aviary, a grand 2.0 version of an older mini flight cage located inside the Nut Tree’s former eatery, was singularly designed as the gateway to the new restaurant. To enter, visitors passed through a portal surrounded by the glass-enclosed aviary. This architectural sequence appears to be historically unique to the Nut Tree, and is still admired by designers today, even though it is no longer. The building was demolished in 2003 by the new owners.

“As a kid, I didn’t know what modernism was, but the architecture at the Nut Tree definitely communicated something meaningful to me. There was an authenticity and originality about it that I believe would be admired even today,” says Vrilakas, whose portfolio includes the Ice Blocks complex on R Street and Oak Park’s flatiron building, among other landscape-defining projects around town. He likens the Nut Tree’s retail/restaurant building to a gleaming airport terminal. “The procession of experiences was really thoughtful. When you entered the building, the dining room was unseen, seemingly tucked in the back, but when you finally arrived there, you were rewarded with a grand space.” This generous volume neatly contained all of the splashy textiles and colorful art, persnickety tabletops and fussy food presentations, among other punchy aesthetics. “There was a two-part focus on elegant simplicity and a paring down to essential components at the Nut Tree,” says Housefield. “Everything counted. Everything had a purpose. And everything was meant to delight.”

*****

One of the last remaining vestiges of the Nut Tree’s heyday, the precast concrete freeway sign, with its stacked triptych of trees made of marble and Italian glass, was dismantled in 2015, drawing the ire of Nut Tree sentimentalists. Lum handed out last paychecks for the remaining employees in January 1996 and says it took her years to return to the site. Birrell, who retired in 1990, occasionally entertained informal requests by a revolving door of new owners to review development plans, brushing off the proposals quickly. “They don’t know what they’re doing,” he’d say.

Automobile advancements are regarded as the main culprit of the Nut Tree’s slow demise, since smoother rides and better gas mileage meant that exiting the freeway for a grab-and-go Yankee Doodle Dog (a frankfurter presented in a striped pouch and garnished with a toothpick bearing a tiny American flag), much less a lengthy sit-down lunch or a meandering train ride, happened less and less over time. What’s more, handheld video game consoles (we’re scowling at you, Nintendo Game Boys) reached widespread popularity in the late 1980s, replacing the amusement-park wonders of the Nut Tree—and roadside attractions everywhere—with hypnotic backseat entertainment.

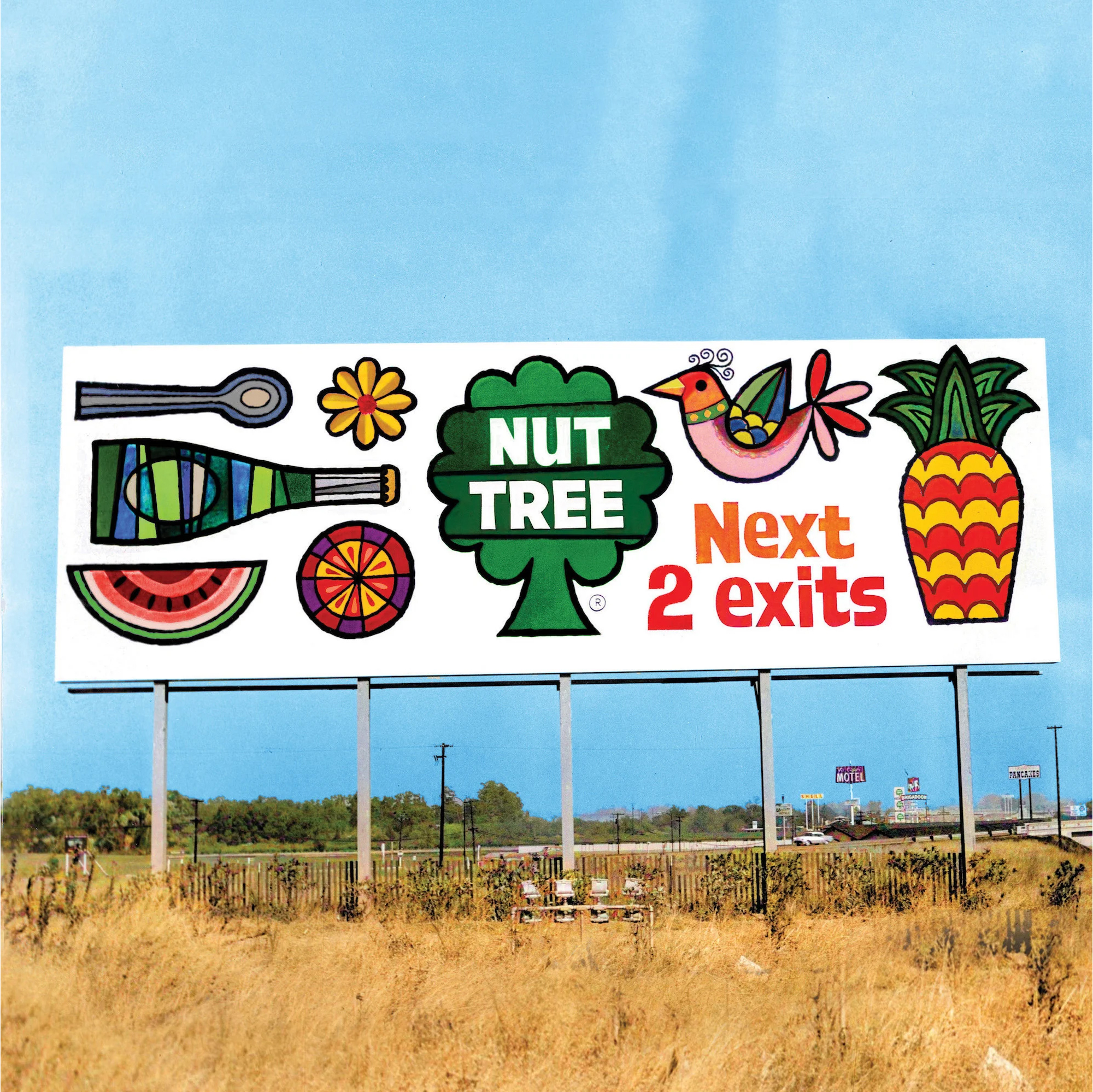

This colorized picture shows a highway billboard sign that beckoned westbound I-80 drivers in 1965 to make a pit stop at the Nut Tree. (Photo courtesy of the Vacaville Museum. Colorized by Dr. Melvin Hale)

The technological invasion only widened an incurable rift among the Power siblings, who suffered irreconcilable creative differences. In fact, Peter Saucerman, a retired partner at Dreyfuss & Blackford, recalls that the architects would sometimes use their understanding of the family fissures—Bob and Ed Jr. didn’t see eye to eye, and their sister Mary Helen often occupied the uncomfortable limbo between them, according to Zimmerman—to thwart a likely sibling standoff about the design. “Albert and Leonard found their rivalries predictable enough to come up with a folly or two,” says Saucerman.

Business debt was hopelessly deepening due to uncut corners, the extreme end result of Bunny and Helen’s originating business philosophy. “What are we doing here if we can’t give people the best?” Birrell would say. He’d often lament about details as seemingly banal as shopping bags, for example—he preferred going the expensive branded route so that guests would continue their remembrances of the Nut Tree even after they drove away, while those watching the bottom line argued for the anonymous brown paper variety. Many of the Nut Tree’s valuable artworks were sold off to ease the burden. Toward the bitter end, consultants were hired and visioning sessions convened to figure out how to revive the Nut Tree’s once thriving experience economy, but to no avail. And yet, musing about the what-ifs has become somewhat of a pastime.

“I’ve reflected on this a lot,” says Lum. “I liken Nut Tree to the Titanic. It was a beautiful, well-crafted, incredible experience with everything it needed to be successful in its time. But like everything else, it was of its time. The world changed. American culture changed.” Having been a passenger on that so-called sinking ship, Lum’s perspective is an intimate one. Housefield, on the other hand, has a different take, from the viewpoint of a design scholar and an outsider who never had the privilege of visiting in person. But his intrigue for the place goes back to his childhood half a country away in Indiana, when his family received a Nut Tree box of dried assorted fruit as a gift. Unwrapping it, he got his first glimpse of Birrell’s artistry and influence neatly displayed under cellophane. “The Nut Tree experience was much more valuable than anything that was being sold there,” he says. “In many ways, that was really remarkable and way ahead of its time.”

Living up to its reputation as an oasis, the vision of the Nut Tree in its brightest days is shimmery at best, as fading memories often are. When pneumonia had consumed Birrell’s strength and he was no longer able to paint or draw in his home art studio, he laid in bed with his eyes closed. Lum stopped by more often in those final days, and noted that his drawing pens were still scattered on his desk. There was an unfinished watercolor mounted on the easel. Everything was getting just a little dustier by the day. Still, a spark of creativity kept flickering. “I asked Don, ‘What is bringing you joy these days?’ ” she recalls. “He just kept his eyes closed and said, ‘I dream.’ ”